Dog Epidemics in Iceland

09.12.2024Evelyn Ýr

So-called dog epidemics or canine plagues have often occurred in Iceland, and they were frequently caused by highly lethal diseases.

Historical records mention outbreaks among dogs in earlier centuries.

In 1591, there are accounts of the deaths of cattle, dogs, and foxes across the country, with the disease reportedly brought to Iceland by an English dog in the western part of the island.

In 1727 and 1728, a canine plague is mentioned in Snæfellsnes, during which livestock also perished rapidly.

Between 1731 and 1733, there are reports of a pestilence affecting cattle, horses, dogs, and foxes. In the travel journal of Eggert Ólafsson and Bjarni Pálsson, the outbreak in South Iceland in 1731 is described: "The dogs and foxes became confused, but not rabid. Foxes wandered toward farms and were killed there."

In 1786, a major canine plague struck Iceland.

In 1827, a deadly epidemic affected dogs, making them so valuable afterward that some farmers were willing to give three sheep for a dog.

In 1855, a canine plague swept through much of the country, devastating entire regions of dogs to the point that it became nearly impossible to herd livestock. It was said that the disease was so contagious that if a healthy dog sniffed a person from a farm where the plague had spread, it would fall ill immediately. The widespread lack of dogs caused significant difficulties, to the extent that a cow or horse was sometimes offered in exchange for a dog. "In the depths of winter, in March and April, 30 people from various northern regions—Bárðardalur, Eyjafjörður, and Skagafjörður—crossed the mountains via Sprengisandur, Eyfirðingavegur, and Kjölur to buy dogs in Árnessýsla and Rangárvallasýsla. The weather was favorable at the time, so the mountain journeys went well."

In 1870, a severe canine plague struck northern Iceland, killing large numbers of dogs and leaving some households entirely without dogs. It was said that the plague had been introduced by an English dog accompanying an English traveler. The disease subsequently spread to western and southern Iceland.

In 1871, Snorri Jónsson, a veterinarian, wrote in Heilbrigðistíðindi:

"The dog is one of those animals that is rarely in short supply here in Iceland, but people only truly realize how much they depend on it when it is absent. When the canine epidemic swept through the country 16 years ago, many experienced how unbearable it is for anyone keeping livestock to be without a dog. This year, it seems that many will face the same situation; for although the dog epidemic has largely subsided in South Iceland, reports suggest it has begun in both North Iceland and the Eastfjords, and it is already proving quite severe. It therefore seems appropriate to say a few words about this disease here, and to touch on the main measures that can be taken to mitigate it."

He further notes that this illness resembles Febris catarrhalis epizootica canum, which is known abroad, except that abroad, the disease only affects dogs younger than one year old. In Iceland, however, it is equally severe for dogs of all ages.

The disease presents itself as follows:

"The illness usually begins with coughing and hoarseness. The nose is dry and hot. At the onset of the disease, clear fluid runs from the nose and eyes, which soon becomes pus-like. This stage can last for several days without the dog appearing very ill; but then the condition gradually worsens. The dog becomes weak, staggers on its legs, experiences seizures, and dies within a fortnight or sooner. Often, this disease is accompanied by severe headaches, causing the dog to act as if rabid—running back and forth, spinning in circles, and sometimes attempting to bite anything in its path. Weakness is always most pronounced in the hindquarters, and it is not uncommon for this weakness to persist even after the dog has otherwise recovered. It is also frequently observed that the dog appears semi-delirious after the illness, particularly if the headaches were severe. Blindness or impaired vision is also a common consequence of this disease."

Snorri continues to urge people to take good care of their dogs, prevent them from coming into contact with healthy dogs, ensure they are not left outside at night, and provide them with sufficient nutritious food, especially meat. He also offers guidelines on various remedies that can be used to treat sick dogs.

In the years 1888, 1892-93, and 1900, epidemics swept across various regions of Iceland, during which numerous dogs were infected and perished.

Source: Description of Iceland by Þorvaldur Thoroddsen. Volume Four, First Issue. 1920.

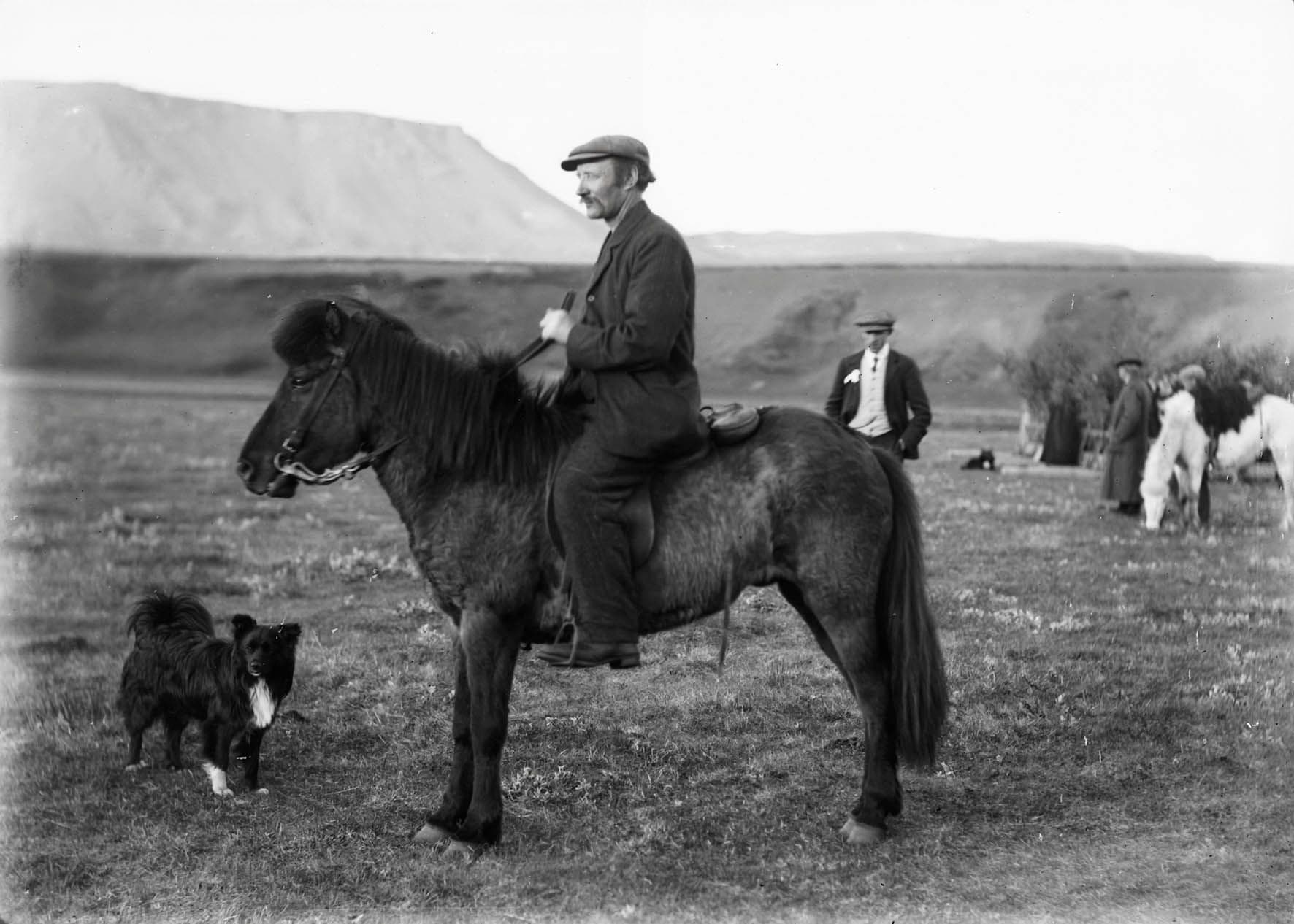

Image: Hallgrímur Árni Gunnlaugsson (b. October 25, 1867), cooper from Raufarhöfn, riding. 1911. Photographer Bárður Sigurðsson.

Contact

Lýtingsstaðir, 561 Varmahlíð.

+354 893 3817

[email protected]